The seven rules that Alexander and his colleagues developed all attempt to guide the urban-design process by fostering a good fit between new construction and the existing environment.' For example, rule 1 -- "piecemeal growth -- says that the best construction increments are small, thus there should be an even mix of small, medium, and large construction projects.1 Building on rule 1, rule 2 -- "the growth of larger wholes" -- directs how specific design projects can be seen to belong together and therefore requires that "every building increment must help to form at least one larger whole in the city, which is both larger and more significant than itself" (pp. 38-39).6

In presenting such specific directives for urban design, Alexander seems to be saying that there must be some sort of reasoned procedure, or instrument as I will call it here, for the actualization of wholeness, which for Alexander is his seven rules through which decision-makers should gain understanding and the city should gain realization.

In contrast, Kemmis appears to have little interest in such a line of practical understanding and clearcut procedure; rather, he seems to believe that, if citizens and politicians begin to put the welfare of their city first, an understanding of what the city is and needs to become will automatically arise through civil discussion, mediation, and compromise: "As citizens become more practiced at working together with the city's best interests at, heart, it is precisely such structures of wholeness that recommend themselves to their attention" (Kemmis, 1995, p. 194).

Alexander might not disagree with this perspective, provided the participants had some degree of conscious awareness of what the wholeness of place is and some set of guidelines to hold this wholeness in mind. On the other hand, Alexander says little about how these directives, through citizen involvement, can actually go forth into building. How, in other words, can his instrument -- the seven rules -- be given direction through various human participants?

In the studio experiment summarized above, the rules were given direction by the students and teachers of the design studio, who role-played a developer/committee relationship founded in dialogue and continual group awareness as to who was planning what where and when. Procedurally, the students were asked to represent developers and community groups, while the studio faculty -- Alexander and his colleagues -- took the role of an "evaluation committee." This committee was responsible for guiding the growth process, and no student "vision" could be constructed until the committee had evaluated the idea and suggested strengths and weaknesses. All faculty and students were involved in all discussions about every project, so there was much mutual understanding as to the project's progress and ultimate aims.'

Obviously, this method of direction is entirely artificial and arbitrary. Ultimately, students had to agree with the judgements of Alexander and the other instructors and to work in relation to the rules whether they personally agreed with them or not. At the same time, the resulting designs were completed only as paper plans and wooden models that never had to face the real-world evaluation of the residents, developers, city officials, politicians, and others who would ultimately provide approval and funding.

In regard to applied direction, this is where Kemmis's ideas are a crucial complement to Alexander's approach: Kemmis provides an extended picture of what is necessary, in terms of getting different parties to discuss and compromise, if urban wholeness and healing is to happen. On the other hand, Kemmis is less aware of how a city works physically and spatially. Again, we come to the basic phenomenological principle that people are immersed in their worlds, which first of all are physical and spatial. The many ways that this materiality supports or stymies human worlds and contributes to or weakens Kemmis's notion of the "good life and the good city" needs the attention provided by Alexander!

In Kemmis's inspiring work, we have the start of a phenomenology of the process by which individuals and groups become the engine for a city of distinctive places, liveliness, and wholeness. At the same time, we must better understand how existing "good cities" work, especially the contribution of material qualities like path layout, arrangement of land uses and activities, qualities of architectural form, and so forth. As a politician, Kemmis emphasizes interpersonal and inter-group process; such a focus is crucial, since it is always human decisions and interventions that in the end build the city.

I am much less certain than Kemmis, however, that citizens putting their place first will always envision the next right move that the city must take to become more whole. An integral part to this healing is precise understanding and expertise grounded in the lived-city, especially its physical, spatial, and environmental base. In this sense, Alexander's design vision is an essential complement to Kemmis's hopeful politics of community and place.

Notes

1. Though he does not say so explicitly, one supposes that Alexander's model of the city is grounded very much in the ideas of urban critic Jane Jacobs (1961), who argued that streets are the heart of the city and should be alive with pedestrian activity that accepts both residents and visitors. Jacobs claimed that the grounding for a vital street life is diversity -- a lively mix of land uses and building types that supports and relies on a dense, varied population of users and activities. She also believed that crucial to diversity and lively streets are qualities of the physical city -e.g., small blocks, direct surveillance from buildings to street, high proportion of built-up areas, and so forth. Note that Jacobs' ideas are also an essential guide for Kemmis' ideas about the city.

2. Kemmis examines the political basis for this argument in his earlier Community and the Politics of Place, which argues for ,a politics which rests upon a mutual recognition by diverse interests that they are bound to each other by their common attachment to a place" (Kemmis, 1990, p. 123).

3. Kernmis more thoroughly discusses the differences between republican and federalist approaches to government in his first book; see Kernmis, 1990, chap. 1.

4. These seven rules are: (1) piecemeal growth; (2) the growth of larger wholes; (3) visions; (4) positive outdoor space; (5) building layout; (6) construction rules; and (7) formation of centers, In studying the rules carefully, one realizes that these rules have two related functions: first, rules 1, 2 and 7 help the designer to recognize and understand environmental wholes; second. rules 3, 4, 5 and 6 help to create new parts in the whole that will lead to healing and a stronger environmental order.

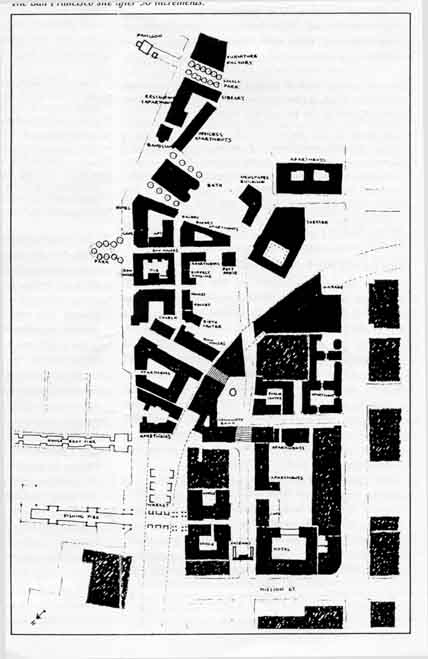

S. In the waterfront simulation, Alexander and his group defined physical size in terms of floor space (less than 1,000 square feet, 1,000- square feet, 10,000-100,000 square feet), while types of uses were defined in terms of "reasonable distribution of functions" (p. 34) The functions of housing, parking, and community were allotted the most space (26, 19, and 15 percent respectively) while manufacturing, shops and restaurants, and hotels allotted the least (12, 7, and 5 percent).

Small projects for the waterfront included fountains, kiosks, gateways and individual houses, while medium projects included a cafe, bakery, row houses, and waterfront park. Yet again, large projects included apartment houses, a theater, a community bank, a main square, an electronics factory, and a pier for ship repairs.

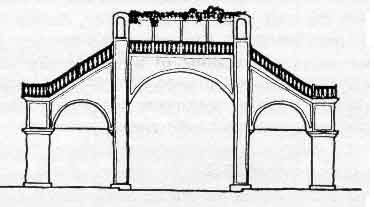

6. For example, the very first project was a high, narrow arching gate to mark the entrance to the site [see drawing on p. 1]. In terms of rule 2, this gate was important because it generated a sense of passage that started beneath the arch and continued south. In this way, the gate hinted at a larger whole -- a street and pedestrian mall going south into the heart of the site. This pedestrian street was then defined more exactly by the next two projects: a hotel and a cafe, which fixed its west side and width (an existing building on the east fixed the street's east side). Soon after, another project -- a community bank -- established the far end of the street, which was then completed by a series of increments that included an apartment house, an office building, and various construction details such as a gravel walk and low wall.

In terms of rule 2, the key point is that each project defining the pedestrian street did several things at once: first, it helped to complete one major center already defined; second, it helped to pin down some other, less clearly defined center; third, it hinted at some entirely new center that would emerge later. One example is the hotel, which wrapped around a garden courtyard. First, in conjunction with the gate, this building helped complete the southern edge of the simulation site; second, it helped to pin down the pedestrian street by fixing its western edge; third, in shaping itself around an outdoor courtyard, it hinted at a new center that in later increments would become a large public garden running south from the hotel and shaped by a series of apartment buildings.

7. Interestingly, Alexander points out that this unspoken agreement became stronger as the students had more experience with the rules: "in the last stages of development, the students were able to function almost entirely without guidance from the committee, since the rules had been completely absorbed and understood" (p. 110).

8. Though here, too, Alexander's picture is incomplete and needs complementary discussion grounded in the efforts of other designers and planners. For example, architects and environment-behavior researchers are only beginning to understand the ways that the spatial patterning of pathways in the city contribute to whether specific streets and districts have or do not have lively, dense pedestrian movement (e.g., Hillier, 1996).

The key point is that the physical design of the city and its districts plays an integral role as to whether urban life will be successful (Seamon, 1994). The dilemma is that, once pathways, buildings, and other physical elements are in place, they are not easily or inexpensively changed. To start with a clear understanding of the physical dimensions of place and to support design and policy that make use of this understanding is therefore crucial from the start of any civil discourse.

References

Alexander, C. 1985. The Production of Houses. New York: Oxford University Press.Alexander, C. 1987. A New Theory of Urban Design. New> York: Oxford University Press.

Alexander, C., Ishikawa, S., & Silverstein, M. 1977. A Pattern Language. New York: Oxford University Press.

Heidegger, M. 1971. Building Dwelling Thinking. In Poetry, Language, and Thought, pp. 145-61. New York: Harper &Row.

Hillier, B., 1996. Space Is a Machine. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Jacobs, J., 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Vintage.

Jacobs, J., 1984. Cities and the Wealth of Nations. New York:

Kemmis, D., 1990. Community and the Politics of Place. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Kemmis, D., 1995. The Good City and the Good Life: Renew ing the Sense of Community. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Seamon, D., 1994. The Life of the Place, Nordisk Arkitelaurforskning [Nordic Jrnl. of Architectural Research], 7, 4:35-48.